Nader Mehravari, Ph.D., Foodways Research Fellow, Center for Iranian Diaspora Studies

The Iranian secular calendar year, which is based the calendar of pre-Zoroastrian Persia, begins on the first day of spring. Astronomically speaking, on this day, the Sun appears directly overhead at the Equator, entering the constellation Aries, marking the start of spring (the vernal equinox) in the Northern Hemisphere.

Persians have been celebrating this annual seasonal transition from winter to spring for more than 3000 years. In the Persian language, this ancient new year celebration is known as Norooz [Persian: نوروز] which translates as “new day” and falls sometime between March 19th and March 21st. This year, the equinox occurs on Tuesday, March 19th at 8:06 pm (PST). The year will be 1403.

Norooz remains the most important secular holiday in Persianate societies. It is celebrated not only by the people who live in the country that today is known as Iran, but also by:

- Communities where some form of the Persian language is spoken including Afghanistan, Azerbaijan, India, Iran, Iraq, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Turkey, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan.

- Iranian diaspora communities around the world.

- People in regions that had been ruled in the past by Persian dynasties (Medes, Achaemenids, Parthians, Sassanians, Safavids, and Qajars).

- Nearby societies that gradually incorporated some degree of Iranian influence into their cultural and/or linguistic traditions such as people in the North Caucasus that were not under direct Iranian rule.

- Communities surrounding the Iranian Plateau where a considerable number of Iranianpeople migrated, such as the Parsi communities in India (Iranian Zoroastrians who migrated to India in 7th century CE) and communities on shores of the Persian Gulf and Gulf of Oman in such countries as Bahrain and United Arab Emirates.

Since ancient times, Norooz celebrations have been intrinsically linked to seasonal changes, as well as food, and drink and the rituals that surround them. Archeological and historical studies have revealed this enduring relationship. Achaemenid records from 6th century BCE Persepolis, inscribed on cuneiform tablets, reveal food distribution orders, including a massive amount of flour – enough to bake bread for 10,000 people – for the New Year.¹ Other examples are the 6th century BCE stone carvings on the walls of a ceremonial staircase in Persepolis that are believed to depict subjects of Darius the Great carrying gifts of vessels of wine for the New Year festival.² In fact, historians have suggested that the elaborate construction ofPersepolis, particularly the Apadana and Hundred Columns Hall, may have been intended to host grand festivities associated with Norooz.

[Photo by Phillip Maiwald, CC BY-SA 3.0]

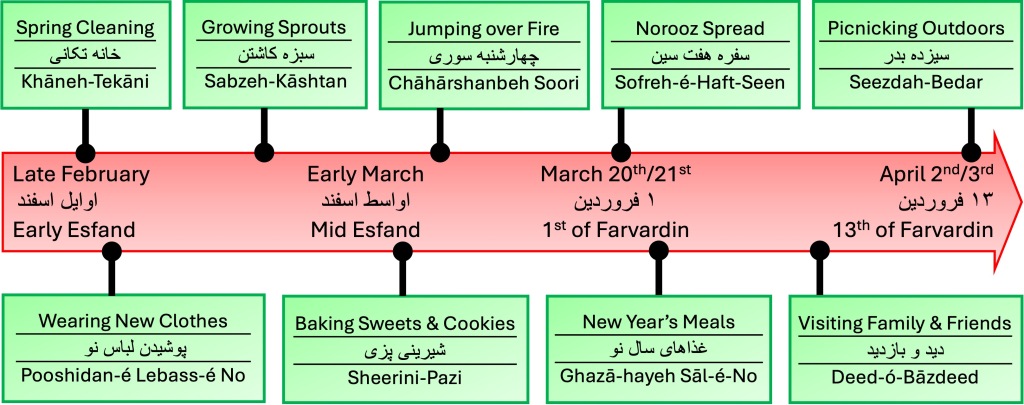

In contemporary times, the inseparability of Norooz and food is evident through most, if not all, phases of Persian New Year celebrations which span nearly two months. As depicted in the timeline below, planning for Norooz typically begins in late February, corresponding to the early parts of the last month in Iranian calendar, Esfand [Persian: اسفند], and concludes early April on the 13th day of the first month in Iranian calendar, Farvardin [Persian: فروردین].

Spring Cleaning – خانه تکانی – Khāneh–Tekāni

With the arrival of Spring, a spirited tradition comes alive in Persianate societies: khāneh–tekāni, literally meaning “shaking the house.” Some historians trace the concept of spring cleaning to this Persian tradition. It’s not your typical spring cleaning, however. In many households, it is a family affair, taking days, with the effort to give a cleaner and livelier look to the living spaces before the arrival of Norooz. The scope of the cleaning is more than just sweeping and dusting. It could involve taking the carpets out and washing them, fluffing up the old-fashioned futon-like mattresses, cleaning drapes and furniture, painting, washing windows, as well as bringing new attention to outdoor spaces, decluttering, and more.

The kitchen gets extra attention, not only to clean and shine, but also to ensure good health in the coming year. Some of the traditional cleaning in the kitchen would have involved whitewashing the heritage copper cooking vessels and breaking and replacing all clay pots that had been used to store food – a act of culinary hygiene dating back centuries.

There are few foods specifically prepared for the khāneh–tekāni period in Iranian households. However, since the khāneh–tekāni days are quite busy with household members performing highly physical activities, high-caloric food items that can be consumed quickly are popular, such as nuts, dates, dried fruit, and halva. Moreover, since the kitchen will be getting a major cleansing, dishes prepared ahead of time are popular such as kotlet (Persian ground meat and potato pan-fried patties), kookoo (class of Persian egg-centric dishes), yogurt, Feta-like cheese, and bread.

Wearing New Clothes – پوشیدن لباس نو – Pooshidan-é Lebass-é-No

The timing of the cleaning and refreshing theme of khāneh–tekāni activities has traditionally been intertwined with another ancient Norooz tradition to make or purchase new clothes for family members, particularly for children. As part of the overall revival theme of Norooz, the tradition is to wear new clothes – at least one piece of new clothing – on New Year’s day.

In addition to buying or making new clothes for family members, there is also the tradition to make new clothes available to the poor and needy. Also, many individuals and families, who might have been dressing in black following the passing of a family member, wear brighter clothes on the occasion of Norooz – particularly on the first day of the New Year.

I have childhood memories of being excited to go out shopping for New Year’s clothes, lebass- é-eid [Persian: لباس عید]. In fact, I still remember the specific department store that we used to go to for clothes, “the Ferdowsi Department Store” [Persian: فروشگاه فردوسی; Romanized: Forooshgah-é-Ferdowsi] – a somewhat fancy store that we would visit at least once a year.

Another related family tradition I used to get excited about had to do with food. The clothes shopping activity was an all-day affair which meant that we would get to eat out – not a typical habit of my childhood years. We went to a Chelow-Kabābi [Persian: چلوکبابی] – a restaurant what would specialize in the famous Persian grilled meats, kabābs. Going to a Chelow-Kabābi was more special because we would get to eat dishes that would normally not be prepared at home.

Growing Sprouts – سبزه کاشتن – Sabzeh-Kāshtan

One of the most visible signs of Persian New Year are the trays and containers of Sabzeh [Persian: سبزه], the vibrant green shoots of wheat, lentil, or barley seeds that are sprouted in preparation for Norooz. The sprouting of life from a seed is perhaps the Persian tradition that most strongly symbolizes growth, renewal of nature, and the arrival of spring.

Growing Sabzeh is primarily a symbolic act, however there is a secondary culinary dimension. Samanoo [Persian: سمنو] is a sweet pudding-like paste that is made from germinated wheatberries. In Iran, Samanoo typically is only made in preparation for Norooz as it is one of required edible elements placed on the altar (Haft-Seen) prepared and placed in the home in anticipation of the vernal equinox – more on this later.

The process of making Samanoo takes about a week. Wheatberries have to be soaked and allowed to germinate and grow. The final stage involves gently cooking the germinated wheatgrass in water for an extended period of time – traditionary overnight – while being constantly stirred.

Jumping over Fire – چهارشنبه سوری – Chāhārshanbeh-Soori

Many of the Norooz preparatory traditions are accomplished within the confines of one’s family and household. The first community-wide activity in anticipation of Norooz takes place on the eve of the last Wednesday of the year of the Iranian calendar – the last Tuesday night of the year. It is called Chāhārshanbeh-Soori [Persian: چهارشنبه سوری] roughly meaning “Fiery Wednesday.”

A few days before this event, people gather (or purchase) easily lit materials for a symbolic fire: kindling, tumble weed, brushwood, date palm leaves (in southern Iran), rice stalks (in northern Iran). In the late afternoon, the community would pool their chosen fuel in bundles within neighborhood alleys or in a designated village square or city street. The bundles, always in odd numbers (one, three, five, or seven), are spaced a few feet apart.

As the sun sets, or shortly thereafter, the bundles are set ablaze. As the bundles burn and flames crackle in the twilight, men, women, and children jump over the fire, chanting ”sorkhie tō as man, zardie man as tō” [Persian: سرخی تو از من، زردی من از تو] (give me your beautiful red color, take away my sickly yellow pallor) referring to the belief that these fires will shield people from illness and troubles that weaken body and spirit. Jumping over the flames is also believed to bring a year of good health and fortune, keeping misfortune away.

There are many culinary traditions accompanying Chāhārshanbeh-Soori ranging from snacks that are shared while the fires are burning to designed dishes served for that evening’s dinner. In particular:

- Ajil [Persian: آجیل] – a special mixture of nuts and dried fruit comprised of seven dried fruits and nuts: pistachios, hazelnuts, raisins, walnuts, apricots, dates, and nectarines.

- Bowls of seven varieties of fresh fruit: oranges, quinces, persimmons, pomegranates, apples, grapes and medlars.

- Reshteh-Polow [Persian: رشته پلو] – Persian steamed rice mixed with toasted wheat noodles

- Āsh-é-Reshteh [Persian: آش رشته] – A thick soup of herbs, legumes, and wheat noodles

Baking Sweets & Cookies – شیرینی پزی – Sheerini-Pazi

Traditionally, starting with the moment of vernal equinox through the following 13 days, many sweets are consumed by Persians as part of the Norooz celebrations. Although they all are delicious any time of the year, some of them are designated as must-haves for Norooz celebrations including:

- Nān-é-Nokhodchi

- Nān-é-Berenji

- Sohān-é-Assali

- Bāghlavā

- Zoolbiā

- Bāmieh

- Toot

Historically households, would spend days baking of cookies, pastries, and other sweet delights in preparation for the arrival of the New Year. These days, however, they can easily be purchased from professional confectioners whose stores become very busy often with queue of customers stretching out into the sidewalk.

Norooz Spread – سفره هفت سین نوروز – Sofreh-é-Haft-Seen

An hour two before the the exact moment of Spring equinox, regardless of what time of the day or night it might be, family members start setting out an elaborate and colorful spread of symbolic and mostly edible items. The spread is called Sofreh-é-Haft-Seen [Persian: نوروزسفره هفت سین] meaning the spread or altar of “seven Ss,” where Sofreh [Persian: سفره] is the term used to refer to a cloth on which the food is served and that people sit around to eat. Seven food items whose name in Persian start with the letter that sound like ‘s’ are carefully arranged on the Sofreh-é-Haft-Seen. Typically, they are:

- Somagh (sumac) for vitality

- Serkeh (vinegar) for patience

- Samanoo (sweet wheat pudding) for abundance

- Sabzi (sprouts) for renewal,

- Seeb (apple) for health

- Seer (garlic) for protection

- Senjed (dried lotus fruit) for love and beauty

The selected items vary from household to household, from region to region, from ethnic group to ethnic group, etc. Collectively, it is believed that they represent seven guardian angels: birth, life, health, happiness, prosperity, beauty, and light.

The Sofreh-é-Haft-Seen also includes many other edible items that do not start with the letter “s” including a medley of fresh fruit, nuts, dried fruit, a wide range of sweets, bread, and colored eggs. Additionally, some nonedible items are key to the New Year’s spread: flowers (usually the fragrant hyancinth), a mirror and burning candles to embody reflection and spreading of light, goldfish in a bowl of water to symbolize the astral symbol Pisces, a book of poems by Persian poet Hafez, and often the household’s religious holy book if they are a practicing family.

At the exact moment of the spring equinox all members of the family gather around their Sofreh- é-Haft-Seen to welcome the arrival of spring and the New Year. Following this, those sitting around the spread exchange greetings, gifts are presented to the younger members of the family, and all share in tasting the sweets on the spread.

New Year’s Meals – غذاهای سال نو – Ghazā–hayeh Sāl-é-No

Traditionally, the families’ first main meal of the New Year is a special one where a selection of New Year’s-specific dishes are served. Traditionally, most New Year’s Day dinners include:

- Persian steamed rice mixed with aromatic green herbs [Persian: سبزی پلو; Romanized: Sabzi-Polow],

- Pan fried fish [Persian: ماهی سرخ شده; Romanized: Mahi-é-Sorkh-Shodeh], and

- Green herb kookoo [Persian: کوکو] which is an egg-centric dish somewhat similar to frittata.

Noodles [Persian: رشته Romanized: Reshteh] have a special cultural significance for New Year’s. Another meaning of the word reshteh in Persian is “thread.” For Persians, noodles symbolize threads of life. Dishes with noodles are often served at Norooz symbolizing strands that mirror the interwoven ties binding families. The two most popular noodle dishes served for the New Year are:

- Reshteh-Polow: Persian steamed rice mixed with toasted wheat noodles

- Āsh-é-Reshteh: A thick soup of herbs, legumes, and wheat noodles

New Year Visits – عید دیدنی – Eid-Didani

The New Year festivities are designed to bring people together. Over the next thirteen-days, friends, neighbors, colleagues, and even acquaintances, both local and distant, visit each other’s homes. These visits are called Eid-Didani [Persian: عید دیدنی] meaning New Year’s visits.Traditionally, Eid-Didani begins by honoring the eldest family members, such as grandparents and older aunts and uncles, with visits during the first few days. Younger relatives, including cousins and younger aunts and uncles, receive visits later. It’s customary for those visited to return the hospitality with a visit of their own.Food plays a primary role in these visits. As soon as guests arrive and have had a chance to sit down, the host serves fresh fruit, snacks of nuts and dried fruit, New Year’s sweets, and hot Persian tea. As part of traditional Persian hospitality rituals, the host will encourage their guests to eat as much as humanly possible.

Picnicking Outdoors – سیزده بدر – Seezdah-Bedar

Norooz celebrations culminate with an epic picnic on Seezdah-Bedar. Seezdah-Bedar means ‘taking out the 13,’ and takes place on the 13th day of the Persian New Year, marking the end of the Norooz celebration. Seezdah-Bedar is the most popular Iranian picnicking occasion. Even Iranians living in other parts of the world picnic on this day. Seezdah-Bedar picnics are all-day events preceded by days of preparation and cooking.When it comes to paraphernalia taken to Seezdah-Bedar picnics, Iranians are not stingy. They often bring along a full set of equipment and supplies to provide day-long comfort, nourishment, and entertainment. Iranians are famous for not only fully loading their car trunk but also cleverly tying picnic necessaries to the roof of their cars. Some of the items are brought to a typical Seezdah-Bedar picnic are carpets, sofreh, cooking gear, tea-making provisions, grills, pillows and blankets, folding chairs and tables, and games like backgammon and balls to kick around.

The central focus of this Iranian picnics is food which can range from simple to elaborate. They might include cold or hot dishes; savory and sweet; and many are prepared ahead of time at home, some bought on the way, and some cooked onsite; including snacks, starters, mains, desserts, and fruit. And, some are brave enough to barbecue their kabob at a picnic sight. Some of the most popular Seezdah-Bedar foods include:

Snacks and starters:

- Ajeel (mixtures of salted and unsalted nuts, seeds, and dried fruit)

- Kahoo-va-Sekanjebeen (Hearts of romaine lettuce dipped in a thick vinegar and mint flavored sweet syrup)

Dishes prepared at home and served at room temperature:

- Māst-ó-Khiār (Yogurt, chopped cucumber, and mint)

- Kotlet (Pan-fried patties of ground lamb, mashed potatoes, and eggs)

- Kookoo-é-Sabzi (Chopped fresh herbs and egg frittata-like crustless-quiche-like dish)

- Traditional Persian sandwiches using the Persian batard-like bread called bolki, stuffed with a variety of cold ingredients – the most famous being mortadella (kālbās)

- Sālād-é-Olivieh (One of the most popular salads of Iranian people, comprised of chopped chicken, potatoes, eggs, sour cucumber pickles mixed with a bit of mustard, some mayonnaise, and lots of olive oil)

Dishes Prepared at Home and Served Warm (either kept warm during transport or warmed up at the picnic site):

- Āsh (A class of thick porridge-like soup of chopped fresh herbs and a medley of legumes; in particular, Āsh-é-Reshteh which is a variety that has Persian wheat-based noodles)

- Polow or Tahchin (A class of Persian steamed rice dishes where the rice is combined with other ingredients during the steaming phase.)

Cooked Onsite:

- Variety of Persian flat bread such as Sangak, Barbari, Lavash, or Taftoon (In Iran, often purchased fresh from neighborhood bakeries on the way to the picnic)

- Persian Feta-like brined white cheese

- Plate of fresh herbs (mint, tarragon, watercress), scallions, and radishes

- Homemade pickles

Endings:

- Fresh fruit including watermelon

- Any leftover Norooz specific sweets

In addition to all the food-centric aspects of Seezdah-Bedar, there are two other important Seezdah-Bedar traditions. Picnickers throw the Sabzeh that they had grown earlier into a body of water, preferably running water, symbolizing the letting go of past burdens and embracing a new beginning. For single women, a silent ceremony may take place to tie a knot with a blade of grass, hoping for a future spouse in the coming year.

[Photo by Pejman Akbarzadeh / Persian Dutch Network, CC BY-SA 3.0]

Closing

Over millennia, from the Achaemenid era to the modern day, Persianate societies have intertwined their Norooz festivities with their culinary traditions, woven together like threads in a rich tapestry of celebration and food. From the early days of spring cleaning to the vibrant fire- jumping of Chāhārshanbeh-Soori and the joyous outdoor gatherings of Seezdah-Bedar, this celebratory thread weaves through months of preparation, anticipation and festivities. It’s a living tapestry, demonstrating the timeless connection between Norooz and food. It is also a season that symbolizes hope. And we wish you—Norooz Pirooz!

- Dandamaev, Muhammad A. and Vladimir G. Lukonin. The Culture and Social Sinstitution of Ancient Iran. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989) 147.

- Floor, Willem M. and Hasn Javadi. Persian Pleasures: How Iranians Relaxed Through the Centuries with Food, Drink & Drugs. (Washington, DC: Mage Publishers, 2019) 168.